I began this project out of an almost compulsive need to catalogue my surroundings. I was in a personal rut with no vision (and not much drive) after I had just moved away from family and home for the first time. I felt disoriented and disconnected from my surroundings- a bit of a tourist in my own life. And so I began photographing whatever I could get my hands on, random things in my apartment that I eventually began to curate down to shards of my life that were significant in a quiet way- small things that seemed insignificant but felt huge. I was photographing like this for a while, using a scanner as a camera, scanning objects I chose.

Growing up in North Louisiana, the majority of my extended family within a few hours’ drive, I’d never realized how physically and emotionally connected I was to my space. In the homes of different members of my family, the shelves were filled with trinkets and relics and stories about their lives. Whenever my mother and my aunts and cousins get together, there’s always conversation about aunts and grandmothers and cousins that I have no memory of. These stories fill up their houses and seem to soak into the furniture. The history and memories are so thick they hang heavy in the air like the humidity.

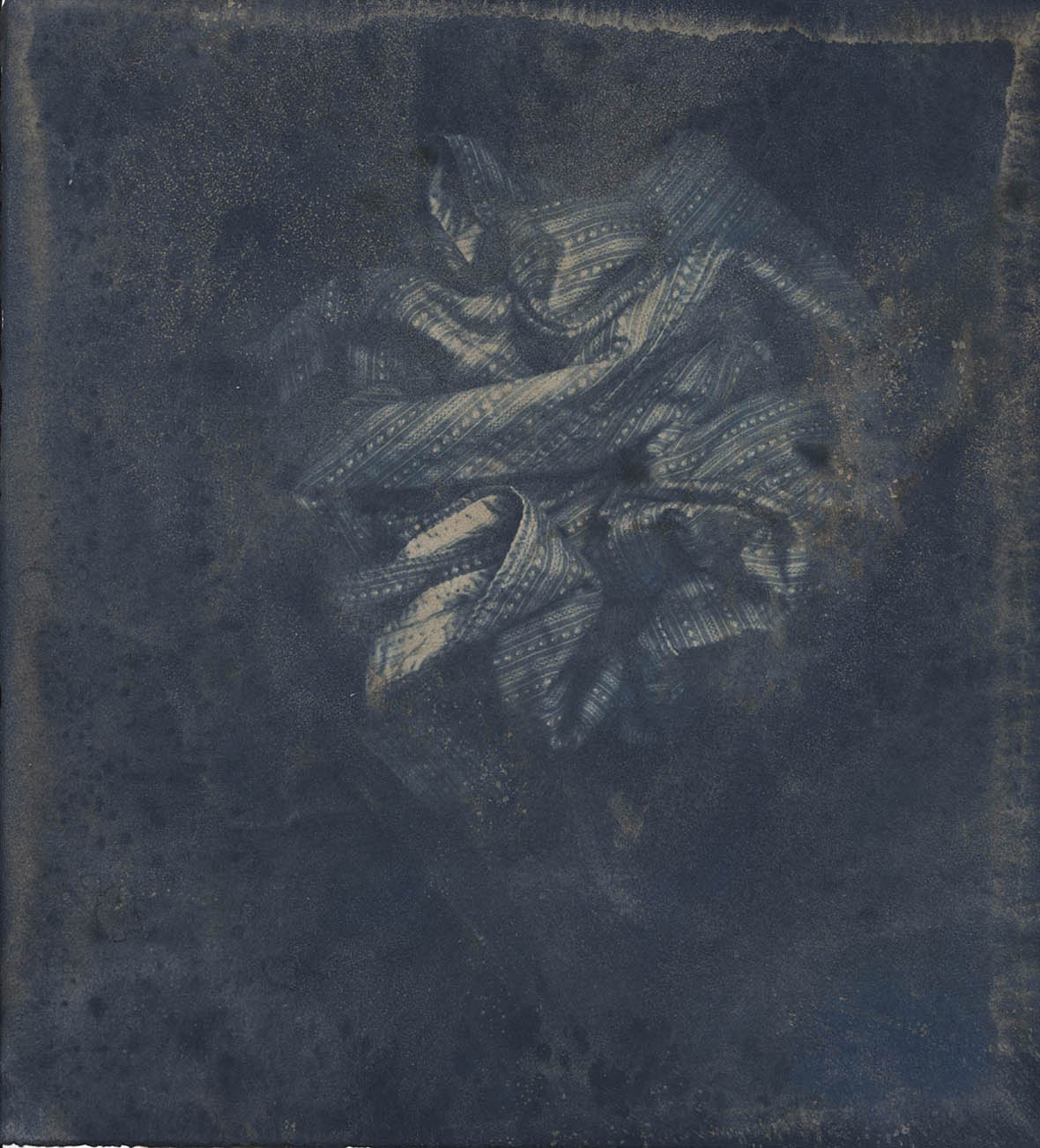

So when I moved away from this home I was confused for a long time about why I didn’t feel connected to where I was or the people I was around. The more I kept photographing and then trying to figure out why I was choosing the pieces I chose, I realized I was trying to reconnect to my own sense of history that I’d been physically removed from. The pieces I felt the most connection to were hand-me-downs from my great-grandmother, Mamaw Jewel. After her death a few years ago, I was given several of her scarves. I only have a few memories of visiting her as a kid, and they’re not especially significant memories, but when I remember her and her scarves, and the sounds her house made and the color of the light in her bedroom, she seemed to embody a time and a world that I was only seeing the last shadows of.

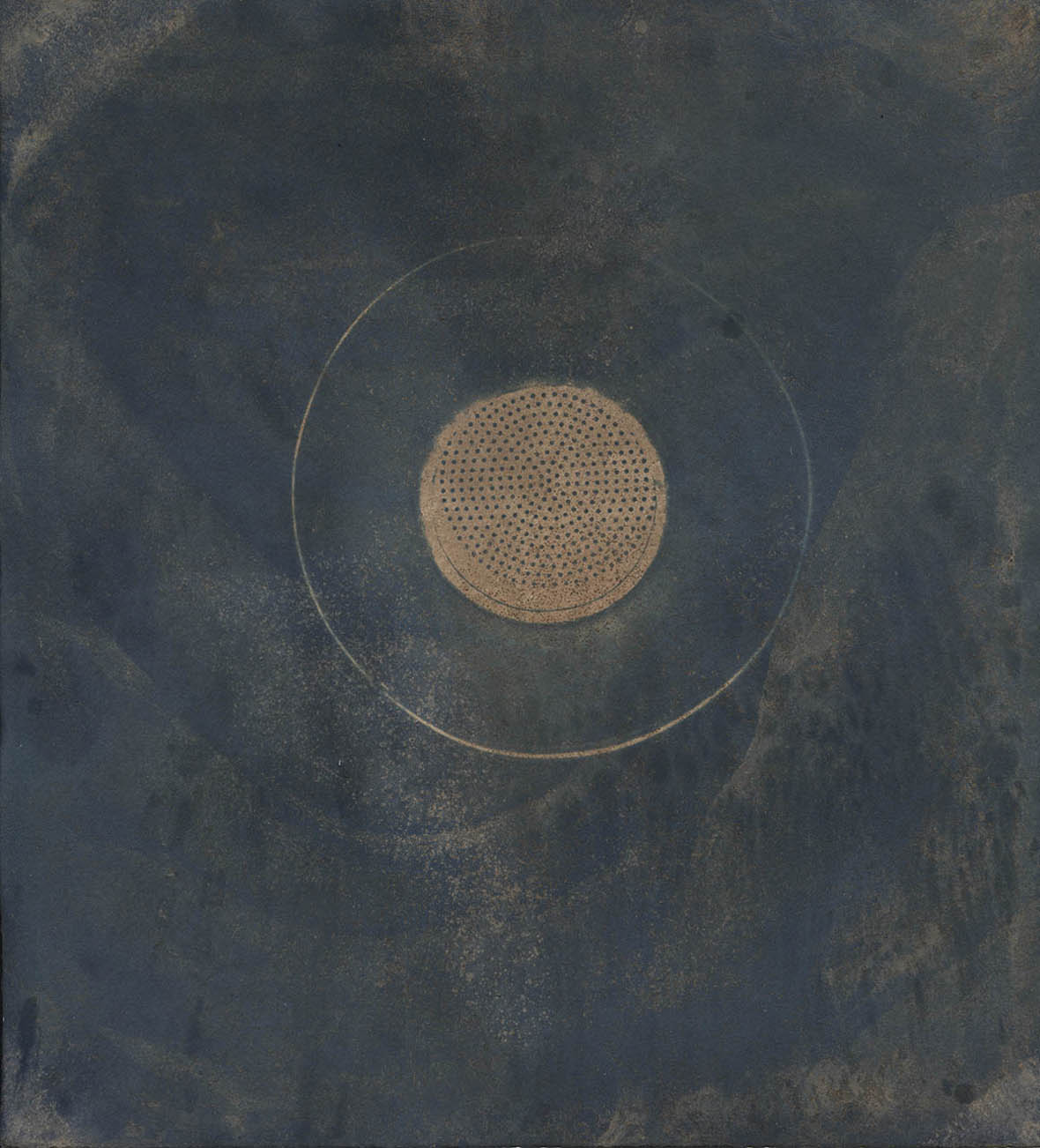

Once I realized what I was really interested in making photographs of, I began asking members of my family for their own treasures, objects they had collected or saved that held the same significance of history and connection for them that these scarves held for me. They began sharing pieces with me that had small memories that could seem insignificant to anyone else, except that my family lived them- the experience these pieces held flows through their veins. And so when my aunt shared with me about how her grandmother always used the same plate when she made fudge and everyone would hover around that plate waiting for it to be filled, I begin to connect a little more. And when they tell me about this little sieve my Mamaw Jewel used when she would prepare meals for her son Paul, who had been left paralyzed after a motorcycle accident when he was 16, I connect a little more.

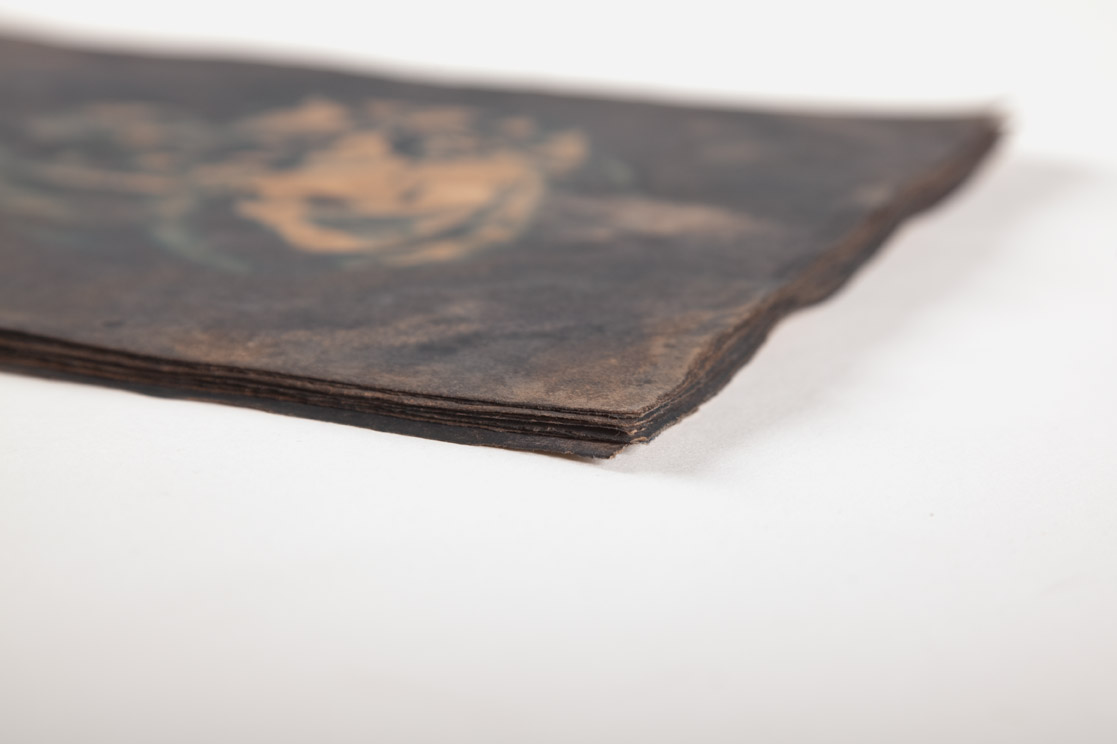

And so, as I was photographing these pieces and weaving myself into the stories they carry with them, I understood that photographing is my way of connecting to these histories and they places they embody, as well as my own way of contributing something of my own to how these pieces exist. Now, These prints are objects in their own right, transcribing the past into a new format that I’ve been able to contribute. I also understood that my method of removing the pieces from any sort of context seemed to mirror the displacement I felt as I made them. I was also very aware that my method of printing and dying was also something significant that this project needed. The amazing simplicity of a cyanotype, the fact that, among photographers, it is seen as an almost disposable process, was completely right for the images I was making. These objects would seem unimpressive to anyone who didn’t own them and experience them- my prints needed to mirror that initial unimpressiveness so that the value of the pieces and the prints could be found in the history they imbue.

The pecan dye serves a similar purpose. Humans have been coloring and dying and staining for centuries. Specific colors and methods have carried certain significance with them that communicate a rank in society or allegiance to a clan, tribe, or nation. The dye used in these prints was made from pecan trees near my apartment, though pecan trees are found all across North Louisiana. I found in this little nut a beautiful connection between my life and my current home to my family and my past. Dying these prints gave them back the context I had removed them from- the dye brought them back to the land and the home I had felt displaced from.

The pecan dye serves a similar purpose. Humans have been coloring and dying and staining for centuries. Specific colors and methods have carried certain significance with them that communicate a rank in society or allegiance to a clan, tribe, or nation. The dye used in these prints was made from pecan trees near my apartment, though pecan trees are found all across North Louisiana. I found in this little nut a beautiful connection between my life and my current home to my family and my past. Dying these prints gave them back the context I had removed them from- the dye brought them back to the land and the home I had felt displaced from.

The Cyanotype process is one of the simpler of the alternative printing methods and this is usually the first process anyone with an interest in historical photography will learn. The light-sensitive chemistry, a combination of Ferric Ammonium Citrate and Potassium Ferricyanide, is coated onto a substrate of some kind, in this case paper but wood and even some fabrics will also hold the chemistry. A negative or an object is then placed directly on top of the coated paper for exposure with UV light- this is known as contact- printing. Once the print is exposed for enough time, it is then washed and left to dry.

Once the cyanotype prints were finished, I brewed my own batch of pecan dye and then dyed the prints similarly to the way you could dye textiles. The hulls and nuts were set to a low boil for several days, until the dye was ready. Prints were mordanted to give the dye permanence, and then placed in the warm dye bath until they reached a satisfying tone and intensity.